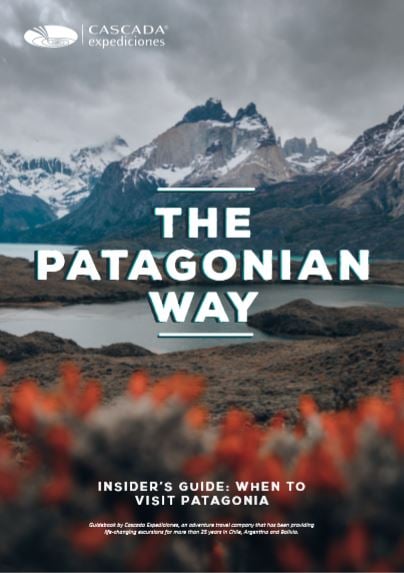

Since its creation in 1959, Torres del Paine National Park never ceased amazing tourists from all around the world, with a yearly increase in visits (almost 300.000 persons visit the park every year since 2017). This wild area of 227.298 hectares – a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve - is amongst Chile’s main protected areas and the efforts of conservation in the park allow a better protection of native species such as the endangered South Andean Deer and pumas.

But the increasing popularity of the “crown jewel of Patagonia” has its downsides. The irresponsible behavior of some tourists caused a couple of huge fires that destroyed a great portion of native forests. Unfortunately, such forests are known for their slow growth and the burnt Nothofagus trees will remain here for about a century before a healthy forest can grow again. These landscapes of devastation can still be seen today around the Grey refuge and Pehoe Lake areas.

In 2005, a Czech tourist accidently overturned a gas stove. The result: about 15,000 hectares of nature burnt (EcoCamp Patagonia was directly threatened by the fire which was fortunately stopped a few hundred meters away from the hotel). In 2011, about 17,000 hectares of the park were affected by a fire caused by a tourist from Israel who burnt toilet paper in the woods at the shore of Grey Lake. Thousands of animals died during these tragic events and all tourists were evacuated from the park.

.jpg?width=1200&name=french%20Valley%20New%20Trail%20(3%20of%201).jpg)

The impact of these tragedies would have been much worse without the sacrifice of hundreds of firemen and park rangers who fought against the fires for weeks. We at EcoCamp were honored to interview Luis Miguel Gonzalez, a Chilean fireman who fought both 2005 and 2011 fires.

This is his story.

The 2005 fire

I have been working for about 18 years as a fireman, specifically with forest fires. I have been working for years with CONAF (Chile’s National Forest Corporation) as a brigade member from 1998. Then I started a contract as brigade leader; my first brigade leader was Eduardo Fuentes who taught me a lot about forest fires. However, I would like to also name some of the persons who shared their experience with me; Hugh Bahamonde, my first head of fire department, Bilibaldo Level head of quadrille, Rene Cifuentes head of fire department, my coworkers Carlos Aravena, Carlos Bahamonde, Eduardo Fuentes, Michael Arcos, Jorge Barría, Francisco Gascogne, Mariela Carrillo, Devora Sanchez, Karina Centurión, Jesica Vasquez, Rodrigo Fernández, Guillermo Santana, Katherine Bahamonde, Victor Agüero and so many others in the Magallanes Region and CONAF workers in Chile’s Metropolitan Region.

Throughout the years I worked with many forest fires in the Magallanes region, the most remembered one being the 2005 fire that started in February, 17th at Laguna Azul in Torres del Paine National Park.

The fire expanded very quickly for days.

We arrived with the Punta Arenas fire brigade during the first night, and immediately understood the scale of the tragedy. I remember seeing the guanacos running on fire, something difficult to process. It was such a terrible loss for the local fauna and flora, in a place that’s so beautiful. I felt a great sense of impotence. Every day we received support from other regions and countries, struggling nonstop with few hours for sleep. It was hard to even find time to eat as we had to fight against the heat and the strong winds. I remember the night when hotels were evacuated as the fire was getting closer to the Estancia (where EcoCamp is located). Rows of cars were leaving the area through Laguna Amarga. That night the fire looked like a tremendous ball of fire lighting the night. The next day, the fire crossed the black bridge, at the entrance of the park. With the help of the Argentine brigade, we tried to stop it but we couldn’t see anything because of the smoke. The waterbomb was working full time in the river so we could not stop fighting even for one second.

For about 24 hours our aim was protecting the entrance of the National Park, Laguna Amarga.

The fire entered a gorge close to the main building. There the wind was hitting really bad and controlling the fire was almost impossible. All of a sudden, we heard an explosion. We could see parts of a mountain refuge flying in the air: a gas bottle has exploded, destroying the small refuge that was there. Everything was covered with smoke and I was totally blind. As I was running away from the fire, I tripped over a rock. Thanks to my working tools, I could stand up and escape towards the main road. My knee was hurting. Thankfully there was an ambulance and I was lucky enough to get an injection both for the pain and inflammation. I immediately kept working but it took us many long days to control the fire in the area. In March, the rain finally started falling which helped us a lot in this hard task. Controlling all the fire hotspots took us a long time so we could make sure the fire was over. 15.000 hectares had just burnt. I could feel a mix of both sadness and happiness.

The 2011 fire

December, 27th 2011. That day I was with the brigade of Puerto Natales when our boss Victor Agüero told us we had to go to Torres del Paine as there was a fire. Everything was packed and we were ready to leave, as the weather conditions that summer were particularly extreme, with strong winds and warm temperatures that were a fertile ground to wildfires.

As the sun was setting we reached Grey lake, that looked like the sea with its huge waves. We had to wait until the catamaran that was used for tourism purpose every day was ready to go. We sailed through the lake and reached the other side of the lake. There we landed with the help of a smaller boat. Due to the violence of the water, we ended up all wet and had to change our clothes. There we faced the fire.

As the wind was blowing hard, we understood the fire was extremely dangerous.

The flames were growing quickly, making the fire even more hostile.

Through the radio, we could hear how fast the fire was growing in other areas of the park. 6 years after the last fire, I was facing another tragedy. Some coworkers were explaining me the news about the fire had gone global, and I was getting how hard this new tragedy was about to hit – once again – the animals and flora of the area. I couldn’t understand how another tourist had started that, this time by throwing away toilet paper – a total nonsense.

In my brigade, there were both men and women working together, with few hours of sleeping and eating. Everything was dry and the wind wouldn’t stop. We set up some firewall lines to fight one side of the fire. We spent new year’s eve inside a tragedy, which wasn’t actually new to me; but it was something shocking for everyone and most of my coworkers had never seen a wildfire like this before.

A minute of silence was our way to “celebrate”. As a fire brigade leader, I did a discourse as a support to everyone. We were living a critique moment – maybe the most important in our career – and our aim was to eradicate the fire while taking care of each other and respecting the norms of security. It was a difficult task considering the scale of the fire, and the fact we had been fighting for a few days already.

Every day before we started, there was a security talk to organize the day’s work. After a few difficult days, we decided to organize shifts so we could rest for 3 days and keep working. That day of January, I joined the group of my coworker Eliecer. We were a group of 8 firemen. We came back to the place of the fire, with a temperature of 23°C/73°F and strong wind gusts. The fire was on a flank and was about to reach a canyon that was leading to a park ranger station. I immediately called a helicopter that unloaded water on a burning tree, which helped us a lot. Unfortunately, the helicopter had to leave, with an average wind speed of 40 km/h / 25mi/h. The 8 of us could prevent the fire from growing. We actually saved a big portion of the area that was covered with native forests. That day we were tired and hungry but proud of that achievement. In the afternoon more fire brigades came in to protect other sectors. We controlled the fire in the area, however the fire had made its way through other areas of the park and even crossed Pehoe Lake toward Laguna Verde, a long way from Grey Lake.

These were long weeks of hard work and controlling the fire was incredibly difficult.

It remembered me how fragile nature is, with the destruction of 17.666 hectares. The rest of the season we safeguarded the park.

And now?

It’s hard for me to tell the story of what happened during a sinister of that magnitude, but what I can tell is the importance of protecting the beautiful fauna and flora that is around us. Humans must be committed to it, while being aware of how much damage we can provoke through our irresponsible behavior.

As far as I am concerned, I know that is was a great life experience. I am grateful no one was hurt and we always worked with the highest standards of safety. This professional experience was something I will never forget, with the noble task to protect nature in the “8th wonder of the world”.

So it never happens again, let’s take care of our national parks.

Luis Miguel Villaroel (center) and his brigade coworkers in Torres del Paine

---

Luis Miguel Gonzalez still works as a fireman, eager to keep studying wild fires. He currently works with a fire brigade in Santiago (Parque Metropolitano) and he is a member of the Wildlife Functional Training. He likes to say that despite the psychological and physical risks of his job, “the protection of nature is the best work in the world”.